Tanner Montague came to town from Seattle having never owned his own music venue before. He’s a musician himself, so he has a pretty good sense of good music, but he also wandered into a crowded music scene filled with concert venues large and small.But the owner of Green Room thinks he found a void in the market. It’s lacking, he says, in places serving between 200 and 500 people, a sweet spot he thinks could be a draw for both some national acts not quite big enough yet for arena gigs and local acts looking for a launching pad.“I felt that size would do well in the city to offer more options,” he says. “My goal was to A, bring another option for national acts but then, B, have a great spot for local bands to start.”Right or wrong, something seems to be working, he says. He’s got a full calendar of concerts booked out several months. How did he, as a newcomer to the market in an industry filled with competition, get the attention of the local concertgoer?

Man with a plan

Man with a plan

When Alberto Monserrate saw a need, he formed LCN Media

by Liz Wolf

Three years ago, when Alberto Monserrate was pounding the pavement selling advertising for small Latino publications in Minnesota, many big advertisers were laughing.

“They couldn’t help themselves,” says Monserrate, president and CEO of Latino Communications Network (LCN Media) in Minneapolis. “They’d say, ‘Hispanics in Minnesota? You gotta be kidding.’ They didn’t deem it necessary to advertise to what they thought was a tiny market.”

That, however, was before the release of the 2000 census, which showed the explosion in Minnesota’s Hispanic/Latino population.

“I realized what most people didn’t at that time, how fast the Latino community was growing,” says Puerto Rican-born Monserrate, 37. “I would drive down Lake Street, and I could see that every week more Latinos were moving in and more businesses were opening.”

But when the numbers were released, even Monserrate was surprised. Between 1990 and 2000, Minnesota’s Latino population grew 166 percent. Today, there’s an estimated 200,000 Latinos in Minnesota, and even more explosive growth is expected. “If projections are accurate, we’re looking at a population of about 500,000 in 10 years,” Monserrate says. Minnesota ranks among the states with the most rapid growth in Latino population.

“There’s been a huge change in many big companies’ attitudes,” Monserrate says. “Now, it isn’t, ‘Should we advertise to the Latino market?’ but, ‘How should we advertise to the Latino market?’ ”

Monserrate, who came to Minnesota 19 years ago to attend the University of Minnesota, knew there was tremendous opportunity if someone could successfully tap in to this fast-growing segment of the population through effective Spanish-language media. Despite rapid growth in the Latino population in the 1990s, Minnesota was underserved by Latino media.

Monserrate’s goal was to serve the needs of the Latino community by offering all-Spanish publications providing local and national news and entertainment. He also wanted to provide vehicles for Latino and non-Latino businesses to reach this growing community.

In the past three years, he has positioned his young company to target this thriving market. LCN merged in 2002 with Nuestra Gente (renamed Gente de Minnesota by LCN), a weekly, all-Spanish newspaper with a circulation of 15,000. It also acquired full ownership in 2001 of The Minnesota-Iowa Hispanic Directory, a Spanish yellow pages with a circulation of 30,000. In addition, the company launched in 2000 Vida y Sabor, a monthly Latino entertainment magazine with a circulation of 15,000. These products also are offered online. LCN has become Minnesota’s largest Latino publishing company.

But Monserrate isn’t stopping there. He’s scouting additional opportunities, including radio and direct marketing. “For that client who wants to reach the Latino community, we want to be the most effective way,” he says.

The Latino community has taken notice of Monserrate. “I’ve seen his focus unfold,” says Val Vargas, CEO of the Hispanic Chamber of Commerce of Minnesota. “I’m impressed with what he’s accomplished. He’s also very committed to the betterment and economic growth of the community. He’s a leader.”

Monserrate left behind a successful, 10-year financial planning career. First he was at American Express Financial Advisors where he managed retirement plans for Fortune 500 clients, and then at Prudential Securities Inc. where he provided financial advice to individuals, businesses and nonprofits. At Prudential, he partnered up with former client, Puerto Rican-born Miguel Ramos, to launch LCN Media in March 2000.

Armed with a strong investment background, the restless and determined Monserrate was ready to try life as an entrepreneur. “I was financially comfortable where I was at — I’m definitely making less money now than I was making in the financial industry — but I was getting bored,” he says. “Also, I was constantly giving my clients, who were mostly business owners, financial advice and I was a little jealous of what they were doing. I knew at some point in my life, I wanted to do it myself. At 33, I was on track to probably be able to retire at 40, but I needed a change. ”

Ramos, now a shareholder at LCN, was a consultant for governmental agencies and corporations wanting to reach Latinos through the media. “He brought to me the frustration that he felt that here in Minnesota there wasn’t an efficient way to do that,” Monserrate says. “I’ve always been a person who likes to take people’s ideas and turn them into something real. I told him, ‘Let’s do something about it,’ and I wrote up a business plan.”

Monserrate says he gets a lot of satisfaction in taking control of a situation like that. “I think that’s my vocation. I constantly hear good ideas, but a lot of people don’t follow through. I like to create a plan; it makes me feel useful. It’s a way I can distinguish myself from others.”

The next step was coming up with the funding. “We felt we needed about $1 million, but we could start out with a half million,” Monserrate says. He found an investor, who made his money investing in Internet companies. He committed to invest $500,000 in LCN.

“He gave us a check for $50,000, without even signing any papers. It doesn’t sound that long ago, but in those days, things like that were happening. Venture capitalists were giving money away,” Monserrate says.

However, it wasn’t long before LCN was forced to find other means of capital. LCN was launched about the same time the Internet bubble burst. “The whole market crashed, and all of a sudden, the investor didn’t have the liquidity,” Monserrate says.

It was time for LCN to get creative. Monserrate began talking to other investors and received some assistance from the owners of the two existing Minnesota Latino newspapers: La Prensa de Minnesota and Nuestra Gente. LCN also scraped up enough cash to acquire 60 percent of the Hispanic Directory.

“The idea behind LCN from the beginning was to integrate different types of media,” Monserrate explains. “We didn’t really want to start up anything. We wanted to acquire a Latino newspaper, and we wanted a directory. Since we didn’t have the money at that point to buy a newspaper, we partnered with La Prensa and Nuestra Gente and brokered ads for them.”

Monserrate invested his own money in LCN and didn’t take a salary for an entire year. “I realized we were going to be very under-funded and raising money was going to be difficult,” he says. “It was a challenge, but I was looking for a challenge.”

But that challenge also brings with it some anxiety. He says it’s hard at times for him to relax, because he’s invested so much time, energy and money in LCN. “It’s hard not to think about the business. If you slip up anywhere, you can lose everything. There are so many things we’ve gone through.”

He often draws inspiration from his maternal grandfather, who was an entrepreneur in Puerto Rico. He died before Monserrate was born, but Monserrate has heard his story. “He had a sixth-grade education and no money, but he was able to start a grocery store that grew into many stores. He watched the trends and sold the stores before the big supermarkets came in. He then went into importing and then real estate. He was very successful.” But Monserrate also knows his grandfather struggled for many years.

Monserrate’s mother wanted her son to keep his corporate job. “She never wanted me to be an entrepreneur, because she saw the hard things I was going through, and it reminded her of what her father went through,” he says. “But now that she sees the business is going well, she’s OK with it. At least that’s what I hear. She won’t tell me that.”

Monserrate soon discovered there was a niche for a Latino entertainment magazine. “We saw the Hispanic community was young compared to the general population: The average age is 23. We also noticed there was a lot of interest in Latin entertainment.” LCN launched Vida y Sabor, which Monserrate describes as a “Latino City Pages.” At that point, LCN owned the magazine, 60 percent of the directory and was brokering ads for the two papers.

“We sold advertising for those papers with the idea that we wanted to acquire them eventually, and both papers expressed interest,” Monserrate says. “We knew that independent Latino publications in Minnesota were not going to last very long. When you have publications making between $200,000 and $500,000 a year in revenue, you barely have enough to cover your employees’ expenses, so we knew we had to have multiple media.”

That’s a good strategy, says Alberto Avendano, a regional director of the National Association of Hispanic Publications and associate publisher of El Tiempo Latino, a weekly Hispanic newspaper in Washington, D.C. “The market’s there. Hispanic media in this country is growing in terms of economics and influence. What’s needed is to create more corporations and move away from the mom-and-pop papers and into highly professional journalistic products.

“The trend we’re going to see is more solid, well-established media companies reaching this market. The way he’s moving the business is the right way to go. You need entrepreneurs who know the Spanish market and the Spanish mentality.”

Avendano also says the Spanish media business is becoming very competitive. “Big corporations like Knight Ridder are looking at the Hispanic market as a niche market to be explored.” Monserrate was well aware of the threat of bigger players coming to town, and says if LCN wanted to compete, or wanted to have something that was worth buying, it had to make some changes.

To help make those changes, LCN began talking with Minneapolis-based Milestone Growth Fund Inc., a small investment company providing long-term, high-risk financing to minority-owned businesses.

“Milestone, at first, thought we were too risky, but they liked our idea,” Monserrate says. “They reviewed our business plan, but they said they wanted several things before they would invest. One, was that we owned 100 percent of the directory. Two, was that we owned 100 percent of a newspaper, and three, we had to fund both ourselves.”

“When Alberto came to us, he owned the magazine, but he didn’t control the yellow pages and only had a joint venture with a newspaper,” says Esperanza Guerrero-Anderson, Milestone president and CEO. “The attractiveness was to have all these units under one CEO, one strategy and one financial reporting system.”

However, she recognized LCN’s potential. “They had a very clear vision of where they wanted to be. They want to be the premier Latino communications company in the region, and their vision is growing by acquiring. We liked their vision, their growth strategy and their different venues.”

Monserrate called a former client to invest, so he could finance the purchase of the remaining 40 percent of the directory. LCN also began working closer with Nuestra Gente. After many months of negotiations, Monserrate and Nuestra Gente’s owner, Juan Carlos Alanis, agreed to a deal. “It was an asset sale, but it really was a merger of equals,” Monserrate says.

He says Milestone encouraged LCN to own whatever it could. Alanis only wanted to sell 49 percent of the newspaper and Milestone said, “ ‘No, either you buy 100 percent or nothing.’ In order for him to agree, it took quite a bit of convincing, and he got 30 percent of LCN, plus cash out of the deal.” (LCN also tried to acquire La Prensa, but couldn’t come up with an agreement. LCN no longer brokers ads for that paper.)

Alanis stayed on as LCN’s vice president of production. Monserrate and Alanis each own 30 percent of LCN, while the other 40 percent is owned by smaller investors. Mario Duarte, editor and publisher of La Prensa, which Monserrate now considers a competitor, owns a small share of LCN. Seventy-seven percent of the company is owned by Latinos.

“It’s incredible, all they’ve accomplished,” Guerrero-Anderson says. “We’re crazy about this company.”

Something else that impressed Milestone was LCN’s willingness to listen to new ideas. “They’re very receptive to suggestions, and that’s unusual for entrepreneurs,” says Judy Romlin, Milestone’s vice president, investments. “You’re an entrepreneur because you want to do it your way.” LCN was receptive, for example, to having an advisory board of directors. “They’re interested in working with senior people to help shape the direction of the company,” Guerrero-Anderson adds.

Milestone Growth invested $250,000 in LCN, but Monserrate says it really wasn’t about the money.

“The thing I liked about them the most was not the funding — because I had other investors willing to invest the same amount — it was their contact list and consulting services,” Monserrate says. The firm helped LCN pay for a part-time CFO, John Erickson, formerly a CFO with Honeywell and U.S. Bank before retiring.

“He’s been an incredible amount of help, giving me all sorts of financial and management advice,” Monserrate says.

“We have a very good relationship,” Erickson says. “Alberto’s very bright and people like him. He’s well known in the Hispanic community and wants to expand beyond that to non-Hispanic businesses looking to reach the Hispanic community. He’s only in his 30s, but he has a fire in his belly. He wants to be creative, he wants to be successful and he wants to grow.”

At this point, 70 percent of LCN’s advertising revenue comes from Latino businesses, but Monserrate believes the future potential is in non-Latino corporations looking to tap in to the explosive market. Many advertisers, however, are unsure how to effectively reach this market, because they don’t understand the demographics and backgrounds of its members, Monserrate says. That’s where LCN’s expertise comes in, he says. LCN is comprised of professionals from all over Latin America and the United States.

Big companies — such as TCF Bank, Wells Fargo, Time Warner, State Farm Insurance and Metro Transit — have become advertisers with LCN, and Monserrate knows there are many more prospects out there. He estimates that only between $1 million and $2 million a year currently is spent in Minnesota by non-Latino businesses advertising directly to Latinos. “This is the same thing that’s happening nationally. There’s only about $1 billion spent in advertising to Latinos.” He believes that’s going to change.

Before the merger with Nuestra Gente, LCN had revenue of $500,000. The company is on track to do $1 million in 2003, and Monserrate expects to grow at least another 50 percent in 2004. LCN also has expanded its staff from three to 14 full-time employees.

“We’ve been profitable since January, and we’ve made some heavy investments,” Monserrate says. “One of the things as an investor I’ve always believed in, is if you have the opportunity in the middle of a recession to make some major investments, you’re going to be in pretty good shape when the economy recovers.”

LCN’s goal is to reach every Minnesota community with a significant Latino population. Monserrate also recognizes potential to expand to other states, but says he’ll be selective.

“The idea is to find places like Minnesota where the Latino community is growing very rapidly, but there isn’t much Latino media to speak of. Chicago, New York, Miami are all cities with huge Latino populations, but the media is already there. These are places where the competition is just too great.”

LCN is looking at Midwestern states like Iowa and Wisconsin, and Southern states like Alabama, Kentucky and Mississippi.

“The idea,” he says, “has always been let’s do it right in Minnesota, and once we learn how to do it here, we’ll go on to other places.”

Cover Story Articles

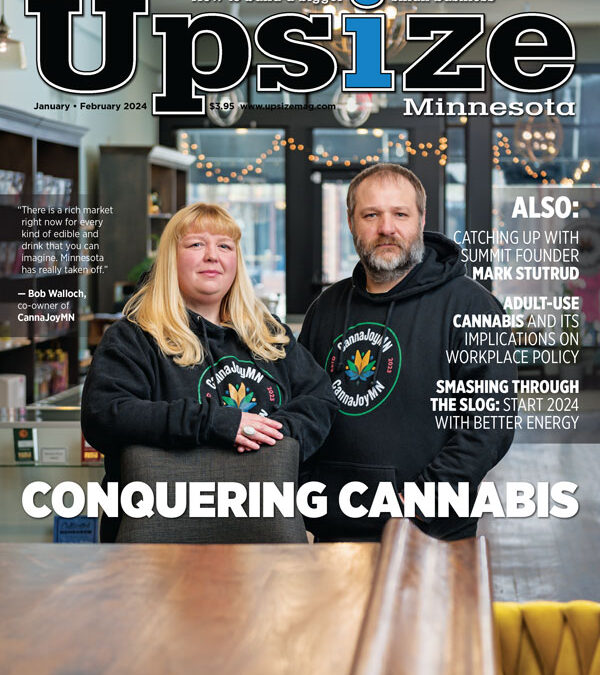

Conquering Cannabis

Pandemic pivots

Demanding diversity

Beehive Strategic Communication helps business owners solve complex challenges thus helping them grow. But the communications firm has been working for more than a decade to do a better job on its own of being conscious of diversity, equity and inclusion (DEI) as part of its business practices.